Winter 2018

Our Partners Make the Difference

By Jennifer Harper, Reserve Manager

Partnerships and collaboration are essential to the function and success of the Reserve’s programs. It is a fact that we are always trying to do more with less. Often there are limitations on staff time, expertise, equipment or funding to accomplish all the goals that we set for ourselves. That is why we value our partnerships so highly. I’d like to highlight just a couple of efforts here, but know that we rely on collaboration and support from many state and federal agencies, local government, non-governmental organizations and professional groups.

The Apalachicola NERR, along with the Grand Bay NERR and Weeks Bay NERR, has been part of the Northern Gulf of Mexico Sentinel Site Cooperative (Cooperative) since 2014. The Cooperative is an effort to identify gaps and needs related to sea level rise (SLR) and coastal inundation in the Gulf. The Cooperative brings together researchers and natural resource managers to prioritize research, collect or synthesize existing data, and bring the best available information and tools to the public. You can learn more about the Cooperative and search for SLR tools/resources on their website at http://masgc.org/northern-gulf-of-mexico-sentinel-site-co. Apalachicola-specific SLR visualizations can also be found there.

Another very successful partnership has been with Audubon Florida. Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, a large amount of restoration funding has gone to preserving and improving habitat for listed species that were impacted during the spill. Shorebirds (and many other species) rely on beaches and coastal areas for foraging and nesting. Through several funding sources, Audubon has increased monitoring and protection of Critical Wildlife Areas (CWAs) and other important nesting areas throughout the panhandle of Florida. Through a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Audubon is helping the Reserve protect the St. George Island Causeway CWA by stabilizing the degrading seawall, increasing signage, and installing fencing to lower chick mortality. These improvements will help the causeway remain a resilient and productive area into the future.

Monitoring the Local American Oystercatcher

By Caitlin Snyder, Stewardship & GIS Specialist

The American oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) had several successful breeding sites in the Franklin County area in 2017. At least seven chicks fledged (capable of flight) from local monitoring sites, during the nesting season which runs from March through August. Although monitoring efforts have varied over the years, the number of fledgings is great news considering that prior observations have totaled only twelve fledged oystercatcher chicks in the county between 2011 and 2015.

American oystercatchers are large, black and white shorebirds that inhabit shores of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. These solitary birds forage and nest on beaches, dunes, salt marshes, mudflats, and dredge spoil islands. They use their strong, red-orange beaks to feed on clams, oysters and mussels. American oystercatchers are protected in Florida as state-listed threatened. As a result, public land managers like the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR) collaborate with Audubon Florida and the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) to carefully monitor breeding activity, assess their local populations and mitigate threats, if possible.

An oystercatcher nest, a depression in the sand, with eggs.

Oystercatchers, among other shorebird species, are sensitive to human disturbances including pets and boats, and to loss, degradation, or development of their beach habitats. Suitable nest sites, such as high sandy and shell areas, can be in short supply, forcing oystercatchers to nest very close to the high-tide line. American oystercatchers scrape out a shallow depression in the sand to lay their eggs, which may take up to a month to hatch. Scrapes and nests are often very cryptic in the shell hash and very susceptible to predators and foot traffic. Chicks are mobile and leave the nest within hours after hatching, though they remain dependent on adults for food for at least two months. Young become flight capable around 35 days.

The Florida Park Service and Audubon Shorebird Partnership has a banding permit from FWC to conduct shorebird monitoring and banding of snowy plover, wilson’s plover, and American oystercatcher. Chicks are typically hand-captured for banding just before they fledge from the nesting site. Banded individuals can provide valuable information on spatial distribution and movement. Local and state land managers use this information to collaborate on conservation efforts.

An oystercatcher hatchling. Fledglings banded last summer have been resighted several times.

This summer, ANERR stewardship staff had the opportunity to assist the Florida Park Service and Audubon Florida with banding two oystercatcher chicks at a new site that had never officially been included in annual Florida Shorebird Database surveys. Earlier in the spring, ANERR staff observed adult behaviors that indicated breeding activity at the new, albeit tiny, site located inshore off of St. George Island. Audubon confirmed a nest with eggs in April and volunteers continued surveying weekly throughout the early summer – the chicks even persevered through Tropical Storm Cindy in mid-June. After a brief round-up effort with several kayaks, the two large chicks were caught, measured, and successfully tagged with unique identification bands on their legs.

Shorebirds and seabirds are monitored year-round by Audubon and volunteers at several important sites across Franklin County, including Lanark Reef, Dog Island, St. George Island State Park, Little St. George Island, Bird Island, Flag Island, and the old SGI Causeway. Causes of nest failure in these areas often are predation, tide/storm overwash and flushing of adults off of nests by boats, people, and pets. Not only is it essential to protect key nesting areas, but also to increase shorebird awareness at a larger scale across the Gulf and Atlantic coastlines to preserve migrant stopovers and foraging areas. The oystercatcher fledglings banded this summer have already been resighted (identified by the unique bands fastened on the legs) several times in the panhandle by Audubon staff and volunteers.

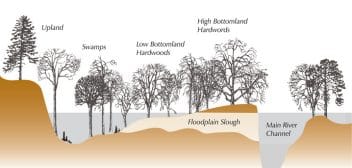

A floodplain is a broad, flat area that surrounds a river’s main channel and can stretch for miles on either side of the channel. Credit Helen Light, US Geological Survey.

Thanks to all of our partners, volunteers, staff and community members for a great team effort on this project – surveying, educating, posting signs, banding, and resighting!

How can you help? Posted nesting areas should be avoided during breeding season, generally February-September. It is recommended that people stay about 300 feet away from birds whether on foot or on boat, so birders need to get out those long-range scopes and enjoy from a respectable distance!

Natural Flood Control

Recent events have shown the value of floodplains

Byline

Floodplains are incredibly important ecosystems that provide nutrients and habitat for thousands of species in a river system like the Apalachicola River. Floodplains also serve as natural reservoirs slowing and holding floodwaters until the water can return to the river channel or be absorbed by wetlands rather than flooding streets and homes.

A floodplain is a broad, flat area that surrounds a river’s main channel and can stretch for miles on either side of the channel. When a river floods, water overflows the main channel spreading out onto the adjacent land filling wetlands, sloughs and streams. When high water levels subside, the river returns to the main channel and water in the floodplain eventually seeps into the ground or finds its way back to the river. All rivers experience periodic high-water flows and it is part of a natural process. If the natural functions of the river are impeded, flooding can result.

The EPA estimates a one-acre wetland can typically store about three-acre feet of water, or one million gallons. An acre-foot is one acre of land, about three-quarters the size of a football field, covered one foot deep in water. Wetlands also help slow and store flood waters reducing the velocity of the water and its destructive potential (EPA, 2006).

Historically many cities have developed in or near floodplains. Photo: Isaac Lang

Historically many cities have developed in or near floodplains. These broad, flat expanses are very fertile and attractive to build on during dry conditions. When flooding occurred, cities implemented flood control measures such as dams, reservoirs, and levees. These measures have been successful but have limits. Recent events have shown us the value of a functioning floodplain. When Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, it dumped 60 inches of rain on Houston. An unprecedented nine trillion gallons of water fell over four days. Over 1,600 homes flooded and there were $800 million in insurance claims filed. The disaster was compounded because thousands of homes had been built in the floodplain over the past ten years. Land that was able to hold and slow flood waters became suburban neighborhoods and roads. There was nowhere for the water to go.

We are fortunate in Franklin County in that much of the Apalachicola River’s floodplain is undeveloped and retains its natural function. The river flows 106 miles from the Florida/Georgia line to Apalachicola Bay and is one of the largest undammed rivers in the United States. The Apalachicola River floodplain is about 144,000 acres. From the upper, middle and lower sections of the river the floodplain varies from 400 feet wide in the upper sections to 4.5 miles wide in the lower sections. (Edmiston, H. Lee, Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (2008)

The Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) reports that floods are the most common and widespread of all natural disasters and recognizes open space as the most effective way of avoiding flood damage. Through FEMA’s Community Rating System (CRS) program FEMA rewards communities for retaining the natural functions of the floodplain and not developing within it. Communities are rated based on steps the community takes that reduce impacts of disasters. A good rating helps residents save money on flood insurance premiums. Franklin County takes part in the CRS Program and earns points because our floodplain has not been developed and retains its natural functions. Flood policy holders currently save 15% on their flood insurance premiums.

EPA. Office of Water (2006). Wetlands: Protecting Life and Property from Flooding. (EPA843-F-06-001).

Edmiston, H. Lee, Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (2008) A River Meets the Bay:

A Characterization of the Apalachicola River and Bay System, pp 53-55)

The Microscopic Side of Plastic

By Rebecca Domangue, PhD, Research Coordinator

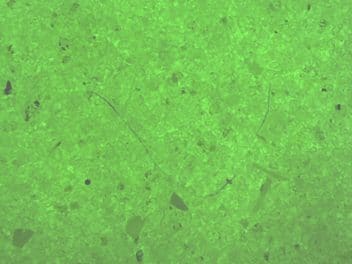

Research coordinator, Dr. Domangue examining microscopic samples of plastic.

In a culture where plastic is synonymous with quick, easy, and cheap, ANERR is taking a deeper look at our relationship with plastics. During the spring, ANERR hosted a visiting artist, Bette Booth and her Splash Trash tour that created beautiful works of art from marine debris collected on local beaches. Not surprisingly, most was plastic. Bette gave a seminar on marine debris and asked the audience to pledge an action to reduce plastic pollution in the ocean by reducing plastic consumption to begin with. I pledged to bring my own takeout container to help reduce plastic waste. Others pledged to bring their own straws (Betsy’s Sunflower shop in Apalach has nice reusable stainless steel ones) or their own grocery bags when shopping. Small but routine changes can make a substantial difference when implemented consistently over time and help keep plastics out of the oceans.

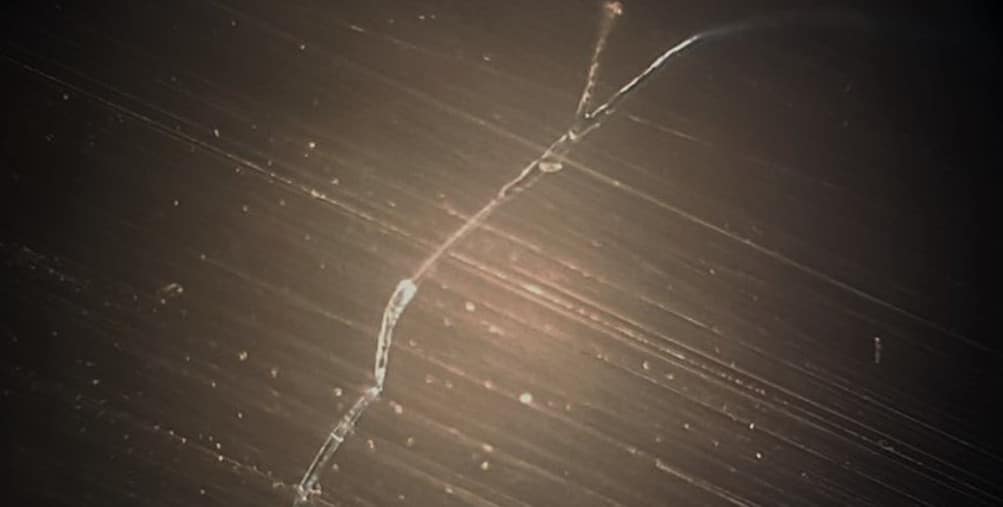

Plastic waste enters the ocean from poorly managed landfills or by carelessly discarded plastic products, or from your very own washing machine and once there it will never fully break down, only become smaller and smaller pieces until it’s characterized as a microplastic. Microplastics are an increasingly abundant type of plastic marine debris characterized as plastic pieces smaller than 5 millimeters that result from the disposal and breakdown of consumer products and industrial waste. They can include pieces from degradation of larger plastic items made from polyethylene, like plastic bags and bottles, polystyrene (food containers), nylon, polypropylene (fabrics), polyvinyl chloride (water pipes), nurdles (pre-production resin pellets used to manufacture plastic items), and microbeads (added as exfoliants to health and beauty products like cleansers and toothpastes). Polyester and acrylic clothing shed more than 1,900 microplastic fibers from one garment during one washing and because of the small size and buoyancy of microplastics, they are not removed by waste water treatment plants and eventually end up in the oceans.

Once the microplastics are in the oceans, these tiny particles never biodegrade and toxins like polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and pesticides in the environment are attracted to and can easily adhere to the surface of microplastics. Microplastics are so small, they are accidentally eaten by marine life, threatening their health.

Preliminary results from Alligator Point show an average of seven microplastic fibers per liter of water and over 400 microplastic fibers per meter square of beach.

For example, the presence of microplastics in commercially grown bivalves in the North Sea contain an average of 0.4 grams of plastic per gram of bivalve tissue indicating how ubiquitous microplastics in the oceans are and the expanse of the problem. Researchers are concerned because the long-term effects of the ingested microplastics with contaminants are poorly understood and there is little information known about whether microplastics bioaccumulate in the food web and eventually impact humans.

Since microplastics are a growing environmental problem and are prevalent in coastal sediments and water of the Northern Gulf of Mexico, ANERR participates in a citizen science microplastics monitoring program in conjunction with Mississippi State University and NOAA’s Marine Debris group that monitors microplastics in water and sand from the Florida Keys to Texas during the annual Coastal Cleanup. This year, ANERR had volunteers at three area beaches collect water and sand samples during the Coastal Cleanup event on September 16th. Researchers are currently analyzing the samples, but preliminary results from Alligator Point show an average of 7 microplastic fibers per liter of water and over 400 microplastic fibers per meter square of beach. Microplastic fragments, film, and microbeads were also present to a lesser extent.

Did you know that you can help keep plastics out of the oceans? Actions you can take to help reduce microplastics in the environment and keep our beaches beautiful and our wildlife healthy include cut back on the use of plastic, especially single-use plastics like water bottles, straws, and cups. Remember reduce, reuse, recycle, refuse. You can see if your personal care products contain plastic (hpd.nlm.nih.gov/, look under personal care) and change brands that don’t use polyethylene microbeads. For example, if your toothpaste has tiny blue spheres in it, those are plastic microbeads that never go away once they are down the sink. You can also wear clothes from natural materials like cotton instead of synthetic fabrics that shed the microfibers during every wash and end up in the sand and water of our local beaches. Moreover, tell your friends and family about the things you can do to reduce plastic waste and encourage them to make some habit and product changes. Like Bette Booth and the Splash Trash tour inspired, we can all make a pledge to reduce our plastic waste in some manner and these small changes will help with the plastic and microplastic pollution problem plaguing the oceans.

Welcome to the Estuary?

By Jeff Dutrow, Education Coordinator

A Covert Quest Into The Mind of a Visitor

The fundamental design and mission of the ANERR Nature Center is to help visitors to understand the answer to the essential question: What is an estuary and why are they important? Accomplishing this mission is a lofty expectation given that a visit more closely resembles a walk in a park than a science test. A visit to the nature center is supposed to be pleasurable. On-line reviews from visitors consistently reflect a wonderful experience with five-star ratings that describe well-maintained exhibits, beautiful boardwalk trails, helpful staff and cleanliness. While such accolades are truly appreciated the greater challenge is to engage visitors’ curiosity and foster understanding about estuaries. Fortunately, estuaries are enjoyable and perfect for curious encounters and generating cool questions seeking answers.

(What is an Estuary) The greeting for visitors to ANERR.

A trip to the Nature Center presents a collection of exhibits somewhat arranged as puzzle pieces seeking assembly. The picture, fully assembled, is intended to model an estuary. The picture visitors often assemble, however, is of the Nature Center building itself as the estuary. Given the relative obscurity of the term this misconception is reasonable. However, the importance of the concept cannot concede understanding when the vitality of the community is dependent on the health of the estuary.

In 2014 ANERR began tracking visitors’ awareness and understanding of estuaries using an online survey. Based on initial data from this survey a new series of exhibits and signs were designed and installed to facilitate better awareness and understanding about estuaries. An essential first component of this effort was the development of the film, “Apalachicola River and Bay, A Connected Ecosystem.” Produced by the Live Oak Production Group, this award-winning film greatly contributes to the visitors’ experience and understanding of the essential components of a healthy estuary. The 12-minute film shows on a rotating schedule in the ANERR Theatre and is also available to view online (YouTube: Apalachicola River and Bay, A Connected Ecosystem).

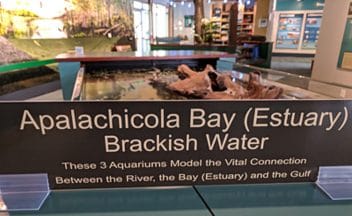

Signage was also added to more clearly describe the three large aquariums in the Nature Center. Always a highlight for visitors, the aquariums are designed to model three essential components of an estuary; fresh water, brackish water and salt water.

(Apalachicola Bay Estuary) Estuary sign on the bay tank in the Nature Center.

The expectation is that the visitors will recognize and connect the three aquariums as model components of an estuary. While this certainly is the case for some visitors it was also apparent that additional directions were necessary to facilitate assembly. Each aquarium now includes signage that describes the water types as well as explicitly stating: “These Three Aquariums Model the Vital Connections Between the River, the Bay (Estuary) and the Gulf.”

An additional effort to raise awareness are two new signs installed on the entrance pathway to the Nature Center. These signs are designed as an overt message for visitors to clearly recognize that understanding the importance of estuaries is the primary outcome of their visit. The signs explicitly state, “What is an Estuary?” and, “Why are Estuaries Important?”. The reverse side of both signs depicts the same message as a prompt for visitors to reflect on their visit and, hopefully, their new understanding about what an estuary is and why they are important.